They will remember that we were sold, but not that we were strong. They will remember that we were bought, but not that we were brave. William Prescott, former slave, 1937

Il traffico di schiavi ha avuto un ruolo determinante nella costruzione della civiltà occidentale, delle sue fortune, del suo splendore.

Il traffico di schiavi ha avuto un ruolo determinante nella costruzione della civiltà occidentale, delle sue fortune, del suo splendore.

Il Merseyside Museum of Liverpool ricorda la storia dei tre secoli di commercio transatlantico, più del 10% del quale passato proprio dal porto inglese – dal 1780 la capitale del traffico di schiavi -, nel bellissimo International Museum of Slavery, aperto nel 2007.

Vi si racconta la storia di milioni di persone (dai 9 ai 15), la cui vita in cattività durava in media cinque anni, durante i quali dovevano subire ogni tipo di violenza e sopraffazione. I testi seguenti sono mie traduzioni dei documenti del Museo, visitato nel luglio 2016.

Indice

1. Introduzione

2. Il Middle passage

3. L’Africa prima dello schiavismo europeo

3.1 Autobiografia di Olaudah Equiano, 1789

4. La cattura e la vendita degli schiavi

4.1 Storia di Okechukwu, Kwame, Oyeladun e Kofi

5. Gli effetti dello schiavismo in Africa [in inglese]

6. I mercanti europei [in inglese]

7. I profitti europei [in inglese]

7.1 I Gladstones di Liverpool

7.1.1 Penrhyn Castle

7.2 Lady Home a Londra

7.3 Thomas Leyland a Liverpool

7.4 Ferrovie

7.5 Miniere d’ardesia

7.6 L’istituto Bluecoat Chambers a Liverpool

8. La gente nera in Europa [in inglese]

9. Liverpool e il commercio degli schiavi [in inglese]

10. La resistenza [in inglese]

11. L’emancipazione [in inglese]

11.1 L’ulteriore oppressione

11.2 La compensazione

11.3 Emancipati ma non liberi

12. Il declino economico [in inglese]

12.1 Le politiche della schiavitù

12.3 Espansionismo e patriottismo

13. Eredità e conseguenze dello schiavismo [in inglese]

13.1 Il razzismo

13.2 Il Ku Klux Klan

14. Il muro delle personalità nere [in inglese]

1. Introduzione al percorso

Gli europei iniziarono ad esplorare l’Africa prima della scoperta dell’America, nel XV secolo: il commercio di schiavi iniziò quasi immediatamente ad opera dei portoghesi.

Gli europei iniziarono ad esplorare l’Africa prima della scoperta dell’America, nel XV secolo: il commercio di schiavi iniziò quasi immediatamente ad opera dei portoghesi.

Non molto tempo dopo, gli africani vennero trasportati attraverso l’Atlantico nelle colonie americane. Poiché la loro cultura e la loro storia erano differenti da quelle europee, i bianchi considerarono gli africani dei barbari e li sottoposero a una brutale oppressione e ad un feroce dispotismo religioso.

Queste credenze razziste, servirono più tardi a giustificare l’intervento coloniale in Africa [Vedi Why Africans?].

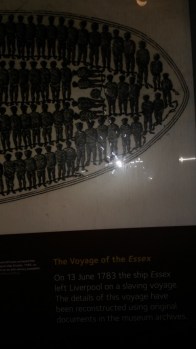

A bordo delle navi, gli africani erano tenuti in condizioni atrocemente disumanizzanti per sei settimane o più (i viaggi cinquecenteschi duravano fino a sei mesi, a seconda delle condizioni del mare).

A bordo delle navi, gli africani erano tenuti in condizioni atrocemente disumanizzanti per sei settimane o più (i viaggi cinquecenteschi duravano fino a sei mesi, a seconda delle condizioni del mare).

Violenza, terrore e degradazione erano un fatto quotidiano a bordo delle navi. Gli uomini erano separati dalle donne e dai bambini. Erano immagazzinati in stive anguste, torride e soffocanti e costretti a danzare durante il viaggio, perché restassero tonici e in buona salute, conservando il loro valore economico.

Le condizioni fisiche, la paura e l’incertezza della propria sorte ne lasciavano molti totalmente traumatizzati e incapaci di mangiare. Alcuni preferivano morire, avvenivano rivolte, il più delle volte senza successo e represse con brutale ferocia, in un viaggio su dieci. Violenza e brutalità si ripercuotevano sul tasso di mortalità dei viaggio che si aggirava intorno al 20/25% di ogni carico [vedi Life on board].

2. The Middle Passage

The triangolar route of slave traders

La tratta degli schiavi seguiva generalmente una rotta triangolare. I commercianti partivano dai porti europei diretti verso l’Africa occidentale, là compravano schiavi scambiandoli con merci che avevano stivato alla partenza dall’Europa.

Il viaggio attraverso l’Atlantico, noto come “Middle Passage”, durava generalmente dalle 6 alle 8 settimane (nel ‘500 poteva durare fino a sei mesi se il mare era sfavorevole). Una volta raggiunta l’America, gli africani

Al loro arrivo nelle Americhe, gli schiavi sopravvissuti al viaggio erano preparati per la vendita come animali.

Erano lavati e sbarbati, a volte la loro pelle veniva oliata per farli sembrare più in salute e accrescere il loro prezzo. A seconda della loro destinazione erano venduti da agenti, con aste pubbliche o in una sorta di zuffa in cui ogni compratore semplicemente prendeva quello che voleva. Le vendite comportavano spesso misurazioni, pesature, ispezioni fisiche intrusive e marchiatura.

Familiari e amici che erano rimasti insieme durante il passaggio atlantico erano spesso separati per sempre. Frequentemente venduti più volte, erano spostati da un posto all’altro prima di raggiungere la loro destinazione finale e dovevano sopportare il trauma di molte separazioni [Branding].

Le navi tornavano poi in Europa cariche di zucchero, caffè, tabacco, riso e più tardi cotone, che erano stati prodotti con il lavoro degli schiavi.

Il triangolo, che toccava tre continenti, era così completato: il capitale europeo, il lavoro africano e la terra americana rifornivano di risorse il mercato europeo.

La storia del commercio transatlantico degli schiavi è la storia di popoli di tutti e tre i continenti toccati nel ‘Middle Passage’.

3. L’Africa prima dello schiavismo europeo

I popoli dell’Africa occidentale avevano sviluppato storia e culture ricche e diverse prima dell’arrivo degli schiavisti europei. Avevano un’ampia varietà di organizzazioni politiche tra le quali regni, città-stato e altre organizzazioni, ognuna con un proprio linguaggio e una specifica cultura.

L’impero di Songhai e il regno del Mali, Benin e Congo erano ampi e potenti con re che erano alla testa di strutture politiche complesse che governavano centinaia di migliaia di sudditi. In altre aree, i sistemi politici erano più deboli e di dimensioni minori limitandosi al governo di villaggi.

Come nel guerreggiato XVI secolo europeo, gli equilibri di potere tra stati e gruppi cambiavano frequentemente.

Arte, educazione e tecnologia fiorivano nel continente africano i cui popoli erano specialmente colti in discipline come la medicina, la matematica e l’astronomia. Erano sviluppate arte e artigianato con produzioni raffinate di vasellame e oggetti domestici in bronzo, avorio, oro, terracotta sia per uso locale che per il commercio.

Gli africani della costa occidentale hanno commerciato con i mercanti europei in Nord’Africa per secoli. I primi mercanti europei a raggiungere le coste occidentali furono i portoghesi nel XV secolo, seguiti dagli olandesi, dagli inglesi, dai francesi e dagli scandinavi. Erano principalmente interessati ai preziosi, quali oro e avorio, e alle spezie, particolarmente al pepe.

Attraverso questi primi contatti, i mercanti europei rapirono e vendettero gli Africani in Europa. Non fu, comunque, prima del XVII secolo, quando i proprietari delle piantagioni cominciarono a domandare sempre più schiavi per soddisfare la crescente domanda di zucchero in Europa, che la tratta transatlantica di schiavi divenne il commercio principale.

Museo Merseyside di Liverpool, Dall’autobiografia di Olaudah Equiano, scritta nel 1789.

4. La cattura e la vendita degli schiavi

I commercianti europei catturavano alcuni Africani attraverso scorrerie lungo le coste, ma la maggior parte degli schiavi erano venduti loro da altri africani o da rivenditori afro-europei [vedi la lettera sottostante]. Tali rivenditori si erano dotati di sofisticate reti di commercio ed alleanze che raccoglievano gruppi di individui per la vendita.

Gentile Signore,

Signore,

Il Capitano John Burrow è arrivato lungo questo fiume il 4 maggio con un ottimo carico, per il quale noi vogliamo più barre di ferro, abiti e polvere da sparo per il carico consegnato al Capitano Burrow in ottobre, consistente in 450 or 460 schiavi.

Spero che la sua nave che trasporta 450 o 460 schiavi, vi arrivi con almeno 340 o 330 di essi. Penso che potrete avere il carico pronto al momento del suo arrivo a Liverpool che stimo per il 15 o 20 Marzo. Inviate perline bianche, verdi e gialle da pagare con denaro, sale e tazze se potete. Spero non ci sia più la guerra in Inghilterra.Vostro affezionato Egboyoung Offeong

Old Calabar, 23 Luglio 1783

mezzi di contenimento

Molti degli africani venduti come schiavi erano stati catturati in battaglia o rapiti, alcuni erano stati ridotti in schiavitù per debiti o per sanzioni. I prigionieri erano condotti sulla costa con marce che duravano giorni, settimane o anche mesi, legati l’uno all’altro. Sulla costa erano imprigionati in fortezze di pietra costruite dalle compagnie di commercio europee o in piccole costruzioni in legno.

Quando arrivavano le navi dall’Europa, erano scambiati con altri beni. I capitani offrivano doni ai capi africani e pagavano loro tributi per poter commerciare in schiavi. Quando il business si fece importante, iniziarono ad offrire loro un’ampia varietà di beni commerciali come tessuti, armi da fuoco, alchool, bigiotteria e conchiglie.

Storia di Okechukwu, Kwame, Oyeladun e Kofi

5. Gli effetti dello schiavismo in Africa

By providing firearms amongst the trade goods, Europeans increased warfare and political instability in West Africa. Some states, such as Asante and Dahomey, grew powerful and wealthy as a result. Other states were completely destroyed and their populations decimated as they were absorbed by rivals. Millions of Africans were forcibly removed from their homes, and towns and villages were depopulated. Many Africans were killed in slaving wars or remained enslaved in Africa.

Many states, including Angola under Queen Nzinga Nbande and Kongo, strongly resisted slavery. However, the interests of those involved in the trade proved too great to overcome.

About two-thirds of the people sold to European traders were men. Fewer women were sold because their skills as farmers and craft workers were crucially important in African societies. The burden of rebuilding their violated communities fell to these women.

“I verily believe that the far greater part of wars, in Africa, would cease, if the Europeans would cease to tempt them, by offering goods for sale. I believe, the captives reserved for sale are fewer than the slain”. John Newton, former slave captain .

People in West Africa have also suffered deeply and they continue to be at a vast disadvantage compared to those who promoted the trade against them. The Reparations Movement is seeking acknowledgment of the horrors committed during slavery. The movement is also demanding financial compensation from Europe and the United States for Africans and people of African descent in the diaspora.

6. I mercanti europei

The main European nations involved in slaving were Portugal, Spain, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. Britain began large-scale slaving through private trading companies in the 1640s. The London-based Royal African Company was the most important and from 1672 had a monopoly of the British trade. Other merchants who wanted to enter this lucrative trade opposed the monopoly and it was ended in 1698.

The main European nations involved in slaving were Portugal, Spain, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. Britain began large-scale slaving through private trading companies in the 1640s. The London-based Royal African Company was the most important and from 1672 had a monopoly of the British trade. Other merchants who wanted to enter this lucrative trade opposed the monopoly and it was ended in 1698.

The number of voyages to Africa made between 1695 and 1807 from each of the main European ports that were involved in the slave trade were:

- Liverpool: 5,300

- London: 3,100

- Bristol: 2,200

- Other European ports: 450 (Amsterdam, Barcelona, Bordeaux, Cadiz, Lisbon and Nantes)

In the early 1700s most of Britain’s slave merchants were from London and Bristol. However, Liverpool merchants were increasingly involved and from about 1740 were outstripping their rivals. Although London, Bristol and other ports continued to send ships to Africa, Liverpool dominated the trade until its abolition in 1807. Indeed Liverpool was the European port most involved in slaving during the 18th century.

In the early 1700s most of Britain’s slave merchants were from London and Bristol. However, Liverpool merchants were increasingly involved and from about 1740 were outstripping their rivals. Although London, Bristol and other ports continued to send ships to Africa, Liverpool dominated the trade until its abolition in 1807. Indeed Liverpool was the European port most involved in slaving during the 18th century.

Find out more about the ‘Ports of the Transatlantic Slave Trade’ in this transcript of the paper given by Anthony Tibbles at the TextPorts Conference, Liverpool Hope University College, April 2000.

7. I profitti europei

Penrhyn Castle

Much of the social life of Western Europe in the 18th century depended on the products of slave labour. In homes and coffee houses, people met over coffee, chocolate or tea, sweetened with Caribbean sugar. They wore clothes made from American cotton and smoked pipes filled with Virginian tobacco. They used furniture made from mahogany and other tropical woods.

Although the profit and loss on individual voyages could vary, many merchants and investors made fortunes from the trade. Many landowners also had estates in the Caribbean, which provided them with large incomes. Though historians disagree about the extent, the profits of slavery and slaving stimulated European economic growth and the growth of capitalism. In particular, the demand for goods to trade in Africa and the goods, particularly cotton, brought back from the Americas encouraged trade and industry in the Midlands and North-West England, the heart of the Industrial Revolution.

The income from slavery and the slave trade made many people wealthy. They built large houses and were able to invest in a wide range of activities, including banking and industry, as well as supporting charitable institutions. Here are a few examples.

7.1 I Gladstones di Liverpool

The Gladstone family had strong connections with slavery. John Gladstone (1764-1851), had large estates in Jamaica and British Guyana and was Chairman of the West India Association. John Gladstone was active in obtaining compensation for slave owners and himself received 93,526.

7.1.1 Penrhyn Castle

Penrhyn Castle near Bangor in North Wales was built for George Hay Dawkins-Pennant. He was a wealthy Jamaican plantation owner who lived in Britain. Penrhyn was designed by Thomas Hopper in 1827 as a vast Neo-Norman castle. It is now owned by the National Trust.

7.2 Lady Home a Londra

Elizabeth Countess of Home was the daughter and heiress of a Jamaican plantation owner. Her first husband died in 1732 and she moved to England and married William, 8th Earl of Home, in 1742. She was a leading member of London society and in 1774 commissioned Robert Adam, the most fashionable architect of the time, to design a house for her in Portman Square. It was one of the grandest houses in London.

Amongst her neighbours in Portman Square were many wealthy people who had profited from slavery including William Beckford, Erle Drax, Lord Maynard and Sir Peter Parker. Admiral Rodney, an opponent of abolition, was another neighbour.

7.3 Thomas Leyland a Liverpool

Thomas Leyland founded the Bank of Leyland and Bullin in 1807. Originally a dealer in food stuffs, he was one of the most active Liverpool slave merchants. Between 1782 and 1807 he was responsible for transporting nearly 3,500 Africans to Jamaica alone. His partner, Bullin, was also a slave trader.

Leyland was reckoned to be one of the three wealthiest men in Liverpool and in 1826 his fortune amounted to 736,531. Leyland and Bullin’s Bank was absorbed by the North and South Wales Bank in 1901 and became part of the Midland Bank (now HSBC) in 1908.

7.4 Ferrovie

Many of the investors and promoters of the Liverpool to Manchester Railway derived much of their wealth from property in the West Indies. These included:

- John Moss, chairman of the committee promoting the railway and later deputy chairman of the company, owned vast sugar plantations in Demerara

- John Gladstone had large estates in Jamaica and British Guyana and received large compensation when slavery was abolished

- General Sir Isaac Gascoyne, MP for Liverpool, 1796-1832, was one of most outspoken opponents of the abolition of the slave trade

7.5 Miniere d’ardesia

Richard Pennant, later Lord Penrhyn, inherited the largest estate in Jamaica. He devoted much of the profits of his plantations to developing the slate quarries of North Wales. He was MP for Liverpool 1767-80 and 1784-90 and spoke forcibly against the campaign to abolish the slave trade.

7.6. L’istituto Bluecoat Chambers a Liverpool

The Bluecoat Chambers in Liverpool was originally built as a charity school in 1717. It was ‘Dedicated to the promotion of Christian Charity and the training of boys in the principles of the Anglican Church.’ The chief supporter of the scheme was Bryan Blundell, who had founded the school in 1708.

Blundell was involved in the Virginian tobacco trade, but was also listed amongst the ‘Company of Merchants trading to Africa’ in 1752. He also transported poor English people to work as indentured labourers in the North American colonies. Blundell was Mayor of Liverpool in 1721.

8. La gente nera in Europa

William Windus, 1844. The boy in this portrait is said to have crossed the Atlantic to Liverpool as a stowaway, and was discovered by William Windus on the doorstep of the Monument Hotel. He was apparently reunited with his parents after a relative saw the portrait in the window of a frame-maker’s shop, although it is not certain if this touching anecdote is true or not.

A few Africans had visited and lived in Europe, including Britain, since Roman times. From the 1450s the Portuguese transported thousands of enslaved Africans to Spain, Portugal and Italy to work as servants or in the fields. Lisbon, for instance, had a significant African population from the 16th century.

As the transatlantic trade developed, ships’ captains and plantation owners brought Africans back to the countries of Northern Europe. They sold them to work, mainly as domestic servants. Many were children.

‘Dear Mama, George Hanger has sent me a black boy eleven years old and very honest, but the Duke don’t like me having a black…. if you like him instead of Michel I will send him, he will be a cheap servant and you will make a Christian of him and a good boy; if you don’t like him they say Lady Rockingham wants one.’

Duchess of Devonshire to her mother, c1790

In Britain Queen Elizabeth was complaining about the number of ‘blackamoores’ as early as 1596. By the mid 18th century London had the largest Black population in Britain, made up of free and enslaved people, as well as many runaways. The total number may have been about 10,000.

It was regarded as fashionable amongst the upper classes to have a Black servant and they sometimes feature in paintings, such as ‘The family of Sir William Young’ by Zoffany. There were Black people in many other towns, such as Liverpool, Bristol, Bath and Lancaster. Smaller number of Black people were also found in rural areas throughout the country.

A number of Black people achieved prominence. Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780) opened his own grocer’s shop in Westminster. He wrote poetry and music and his friends included the novelist Laurence Sterne, David Garrick the actor and the Duke and Duchess of Montague. He is best known for his letters which were published after his death. Others such as Olaudah Equiano and Cuguano were active in the abolition campaigns.

The legal status of enslaved people in Europe was often unclear. In Britain it was not finally resolved until abolition in 1838, though after the famous Somerset case in 1772 enslaved people could not be sent back to the colonies against their will.

9. Liverpool e il commercio degli schiavi

Thomas Leyland (1752 – 1827). He was elected Mayor of Liverpool three times, the first being in 1798. He built up a great fortune, mainly from his involvement in transatlantic slavery, having a financial interest in at least sixty nine slaving voyages. In 1807, Leyland founded the bank of Leyland and Bullin in York Street, Liverpool. Absorbed by the North and South Wales Bank in 1901, it became part of the Midland Bank in 1908.

Liverpool was a major slaving port and its ships and merchants dominated the transatlantic slave trade in the second half of the 18th century. The town and its inhabitants derived great civic and personal wealth from the trade which laid the foundations for the port’s future growth.

The growth of the trade was slow but solid. By the 1730s about 15 ships a year were leaving for Africa and this grew to about 50 a year in the 1750s, rising to just over a 100 in each of the early years of the 1770s. Numbers declined during the American War of Independence (1775-83), but rose to a new peak of 120-130 ships annually in the two decades preceding the abolition of the trade in 1807. Probably three-quarters of all European slaving ships at this period left from Liverpool. Overall, Liverpool ships transported half of the 3 million Africans carried across the Atlantic by British slavers.

The precise reasons for Liverpool’s dominance of the trade are still debated by historians. Some suggest that Liverpool merchants were being pushed out of the other Atlantic trades, such as sugar and tobacco. Others claim that the town’s merchants were more enterprising. A significant factor was the port’s position with ready access via a network of rivers and canals to the goods traded in Africa – textiles from Lancashire and Yorkshire, copper and brass from Staffordshire and Cheshire and guns from Birmingham.

Although Liverpool merchants engaged in many other trades and commodities, involvement in the slave trade pervaded the whole port. Nearly all the principal merchants and citizens of Liverpool, including many of the mayors, were involved. Thomas Golightly (1732-1821), who was first elected to the Town Council in 1770 and became Mayor in 1772-3, is just one example. Several of the town’s MPs invested in the trade and spoke strongly in its favour in Parliament. James Penny, a slave trader, was presented with a magnificent silver epergne in 1792 for speaking in favour of the slave trade to a parliamentary committee.

Although Liverpool merchants engaged in many other trades and commodities, involvement in the slave trade pervaded the whole port. Nearly all the principal merchants and citizens of Liverpool, including many of the mayors, were involved. Thomas Golightly (1732-1821), who was first elected to the Town Council in 1770 and became Mayor in 1772-3, is just one example. Several of the town’s MPs invested in the trade and spoke strongly in its favour in Parliament. James Penny, a slave trader, was presented with a magnificent silver epergne in 1792 for speaking in favour of the slave trade to a parliamentary committee.

It would be wrong to attribute all of Liverpool’s success to the slave trade, but it was undoubtedly the backbone of the town’s prosperity. Historian, David Richardson suggests that slaving and related trades may have occupied a third and possibly a half of Liverpool’s shipping activity in the period 1750 to 1807. The wealth acquired by the town was substantial and the stimulus it gave to trading and industrial development throughout the north-west of England and the Midlands was of crucial importance.

The last British slaver, the Kitty’s Amelia, left Liverpool under Captain Hugh Crow in July 1807. However, even after abolition Liverpool continued to develop the trading connections which had been established by the slave trade, both in Africa and the Americas.

William Roscoe

Petition of Liverpool to the House of Commons, 14 February 1788

Abolition of the transatlantic slave trade

10. La resistenza

Jamaican Slave Revolt (1760-1761): An Interactive Map

11. L’emancipazione

Following a lull after the passing of the Slave Trade Act 1807, the movement towards full emancipation of enslaved Africans by Britain forged ahead. Many abolitions held meetings to discuss the next steps – one such meeting was attended by 2,000 supporters. Despite long-running disagreements between those seeking immediate emancipation and others looking for a more gradual solution, most attendees demanded an immediate end to the slavery system. The committee was a breakaway group from the Quakers’ London Society for the Abolishing the State of Slavery throughout the British Dominions. Itwas created to build up the movement, and soon there were 1,200 local societies. Hundreds of thousands of signatures found their way on to petitions.

11.1 Ulteriore oppressione

The Abolition of Slavery Act, passed in August 1833, was scheduled to come into force in August the following year. The success in having it finally reach the statute books was not entirely due to slave rebellions, grass-roots petitioning and the logistics of military control. The profit motive also had a large bearing.

From the beginning of the abolition movement, its parliamentary supporters had been reassuring planters that emancipation would not affect their labour supply. The promise was held out that those emancipated would remain under some coercion. Vagrancy laws were proposed under which any former slave attempting to leave a plantation would be penalised, and land ownership beyond the range of garden plots would be illegal. There was also to be a period of ‘apprenticeship’ (in the Act’s final draft, a six-year term was agreed on) during which planters had the right to the continuing labour of their ex-slaves.

11.2 La compensazione

The planters were further appeased by the offer of £20 million worth of compensation (nearly £1 billion in today’s money). The emancipation law, from this perspective, was a moderate measure in that it compensated not the slaves, who had built up the wealth of Britain and its colonies through centuries of unpaid labour, but their former owners.

But the lavish compensation paid out to the latter failed to find its way back into developing West Indian island economies. Rather than using these funds to facilitate an effective transition from slavery to free labour, the planters invested them in the British bond and property markets.

11.3 Emancipati ma non liberi

Emancipation Day – Friday, 1 August 1834 – was celebrated throughout the British Caribbean at chapels, churches and government-sanctioned festivals, some of which were held under the watchful eyes of hundreds of extra troops. The previously enslaved populations also awoke to a fresh set of concerns.

A new raft of law-and-order measures had been introduced. Under the new ‘apprenticeships’, newly ‘freed’ people were still expected to remain on the plantations and put in 10-hour days. Absenteeism would result in imprisonment in one of the many new jails (equipped with treadmills) that were being built to contain recalcitrant workers. Additional tiers of ‘special officers’ and stipendiary magistrates were created to police the changes. ‘Apprentices’ could still be flogged without redress, females included.

The apprenticeship scheme would come to an end only in 1838, after the Anti-Slavery Society, following an inspection tour of the West Indian colonies in 1836, had produced another barrage of pamphlets and petitions.

12. Il declino economico

The effects of emancipation in the British West Indies varied from island to island, but the plantation economy declined overall. Yearly sugar production slumped by 36% between 1839 and 1846, but as output dropped, the price of sugar rose and 50% of the Jamaican plantations went out of business. In Trinidad and British Guyana over the next 30 years, the newly freed slaves initiated a series of large-scale strikes. As a result, local planters and government officials imported 96,850 indentured labourers from the Indian subcontinent.

The most positive result of emancipation was the growth of a class of independent Black traders and craftspeople. By 1844, there were 2,500 individuals in this class in Antigua, 6,000 in British Guyana, 12,000 in Barbados and 17,500 in Jamaica.

12.1 Le politiche della schiavitù

In the wake of emancipation, the British government sought to present itself as a roving anti-slavery watchdog. But the ongoing mission to suppress slavery on a global scale also permitted them to monitor the naval ambitions of other European powers. The policing of slavery on the west coast of Africa coincided with a heightening of European interest in the African interior.

The main instrument of this new policy was the British West Africa Squadron. This force of six old ships was unable to monitor the entire coast from Angola to the Cape Verde Islands – the only areas that could be effectively watched were Benin and Sierra Leone. Lord Palmerston once remarked: ‘If there was a particularly old, slow-going tub in the navy, she was sure to be sent to the coast of Africa to try and catch the fast-sailing American clippers.’

There was another problem: only vessels actually carrying slaves could be stopped. Even a ship entering a port with the express intention of slaving was beyond the law.

When African captives were found aboard ships and released, as 35,000 were in the 1830s, the majority ended up being sent to labour in Freetown in Sierra Leone, while the rest consented to travel to the British Caribbean as ‘apprentices’.

12.3 Espansionismo e patriottismo

Some aspects of abolitionism and emancipation dovetailed neatly with expansionist policies and patriotic sentiment. Those like Thomas Buxton were keen to see the regeneration of Africa primarily through a series of trading posts along the River Niger. Buxton’s ideas, as laid out in his 1838 book The African Slave Trade and Its Remedy, quickly gained acceptance among members of the establishment who foresaw the coming of an Africa colonised and controlled by Europeans, though without slavery.

In the wake of abolition, Britain intervened more directly, establishing its first colonies in West Africa: Sierra Leone and then Lagos. This marked the beginning of what would become, by the end of the century, the ‘Scramble for Africa’ – the struggle among European powers to colonise and dominate the continent.

The British carried their new morality with the goods they traded. The abolitionist campaign was taken into the heart of Africa, and gunboat diplomacy was used to encourage African rulers to end the slave trade in their own dominions.

13. Eredità e conseguenze dello schiavismo

Transatlantic slavery changed the history of Europe and its legacy is with us today. Inevitably there is considerable disagreement about the impact of that legacy.

The most obvious result is the presence of millions of people of African descent in Western Europe. Although many have come as a result of migration since 1945, their ancestors were originally transported in the slave trade. Despite individual exceptions, Black people continue to suffer discrimination and to be at a disadvantage in terms of their political, social and economic position. This situation is largely the result of racism developed to justify and sustain transatlantic slavery.

There are obvious examples – the blues, jazz and reggae, some of the most important types of music developed since 1900, were invented by Black people using rhythms and forms of African music. The stories of Brer Rabbit come originally from African folk tales.Black people have enriched the cultures of Europe by introducing traditions and features from their African heritage. Literature, art, music, cooking and language are just some of the areas that have been significantly influenced by people of African descent.

13.1 Razzismo

Francia, 1900. la rappresentazione stereotipata dei neri

Transatlantic slavery also left behind a legacy of racism and other forms of Eurocentrism. Those in the African diaspora and on the African continent found themselves victims of racial discrimination and prejudice, which took a variety of forms.

In the United States, those of African origin were legally declared second-class citizens, forced to accept segregated through Jim Crow laws and often subject to discrimination and racist violence. It took many years of agitation and thousands of deaths before the struggles of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s changed both laws and conditions.

Grate Polish Ads

Africans were also discriminated against by colonial laws, which were based on the racist premise that they were incapable of governing themselves or developing their own land and resources. The most infamous racist regime in Africa, however, was founded on the system of apartheid that was introduced to independent South Africa in 1948. Again, it was only after many heroic sacrifices that it was finally defeated in 1991.

In Britain, too, racism has been a feature of life for centuries. Even in the 20th century, a widespread colour bar existed in accommodation, the armed forces and even boxing – nobody of African origin was permitted to fight for a British title before 1948. Laws against racism were introduced only in 1965. However, hate crimes and institutional racism, such as has been highlighted in the Stephen Lawrence case in 1993 are reminders that racism is a persistent legacy of the transatlantic slavery.

13.2 The Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan is an overtly racist group. Although there have always been different branches, all have a common goal: to maintain the supremacy of the white race over Black people. While membership in the Klan has fluctuated during its history, the scope of its hatred has expanded to add Jews, Catholics, homosexuals and immigrants.

The Ku Klux Klan is an overtly racist group. Although there have always been different branches, all have a common goal: to maintain the supremacy of the white race over Black people. While membership in the Klan has fluctuated during its history, the scope of its hatred has expanded to add Jews, Catholics, homosexuals and immigrants.

The Ku Klux Klan came into existence at the end of the American Civil War in the mid 1860s and lasted until the 1870s. It was organised by ex-confederate soldiers opposed to Reconstruction policies.

The second Klan was founded in 1915 by William J Simmons. The first Klan had been Democratic and southern; the new Klan was more Republican and was influential throughout the United States.

At its height in the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan was responsible for lynching innocent Black men, women and children; even going so far as to murder uniformed Black soldiers returning from World War One.

Since the 1920s the Klan has gone through several revivals, particularly in the 1960s against the Civil Rights Movement, but it has never regained the support it once had.

14. Il muro delle personalità nere

The Black Achievers Wall in the Legacy gallery at the International Slavery Museum is a celebration of Black Achievers past and present. These people represent a real mix of backgrounds, eras and disciplines, from civil rights campaigners and politicians to rock stars and poets. Some are household names like Bob Marley. Others, like rebel slave leader Gaspar Yanga, are virtually unknown to the general public, but all are inspirational.

However, this list is not static, and we want both website and museum visitors to tell us who they think should join the list. Do you think we are missing someone important, or is there an emerging talent you think we should recognise? In collaboration with the Independent we are asking you to send us your suggestions. Remember that your suggestion can come from any era and any background – they could be a sports person, a writer, an activist, a television personality – anyone just as long as they are inspirational.

Commenti recenti